What's so hard to detect about gerrymandering?

After observing the examples in the last section, you wouldn’t be out of line to inquire: “Well, if gerrymandered maps are unusually-shaped, why can’t we just toss out all the weird looking maps?”

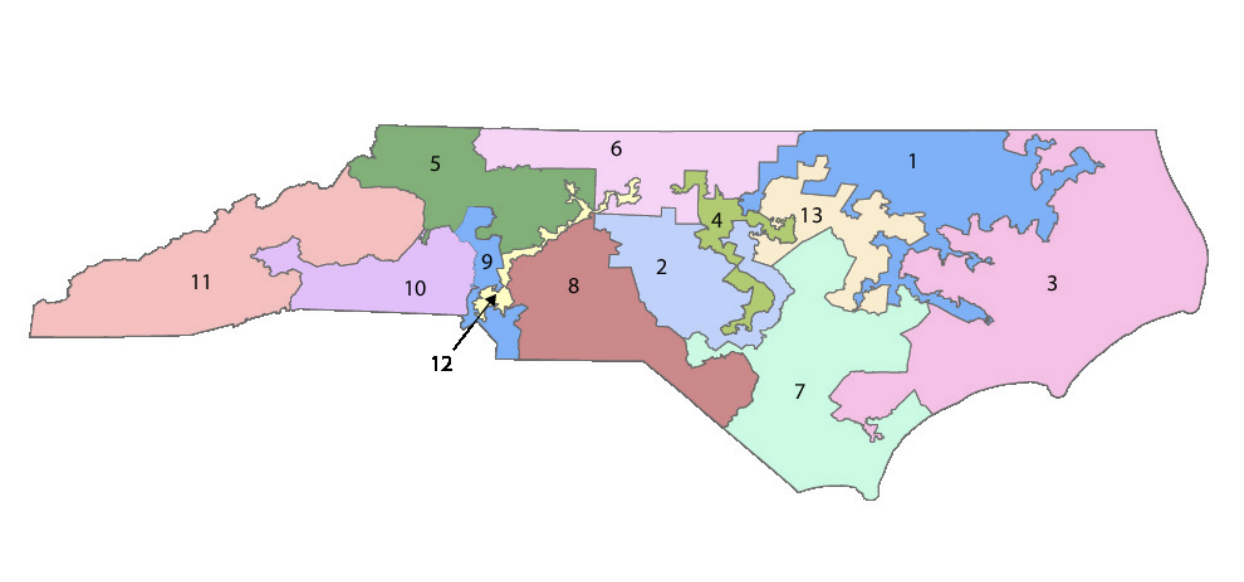

Let me show you another example:

These are districts in North Carolina for the 2012 election. Most of them seem pretty normal/organic in terms of their shape. However, while they may not look the part, these districts are also heavily gerrymandered. And that’s the whole point I’m trying to make here: being oddly-shaped isn’t enough evidence to conclude gerrymandering. Conversely, being normally-shaped isn’t enough evidence to conclude a lack of gerrymandering. This sword cuts both ways.

I bring up this counterexample to highlight the initial complexity of this problem. We can’t simply eyeball maps and toss them out if they look weird. It is certainly possible that they were not gerrymandered at all. And similarly, we can’t approve a map because it looks “normal” to us - it could be heavily gerrymandered. There are age-old adages relevant to this situation: “all that glitters is not gold” and “never judge a book by its cover.”

It’s only logical to then ask: “what’s the solution if we can’t use the eye-test? How do we figure out whether or not a map is gerrymandered?”

Thank you for asking - allow me to answer another question first and then get back to that question (since it is the overarching question of this project). The other question in this case is “what’s the big deal about gerrymandering? What’s so hard to detect in the first place?”

Now we’re talking. Earlier, through the counterexample, I highlighted the initial complexity of determining gerrymandered maps; the idea that there is no level of weirdness that can definitively tell us a map is rigged. Now we can build upon that complexity and show that this problem is worse than you expected.

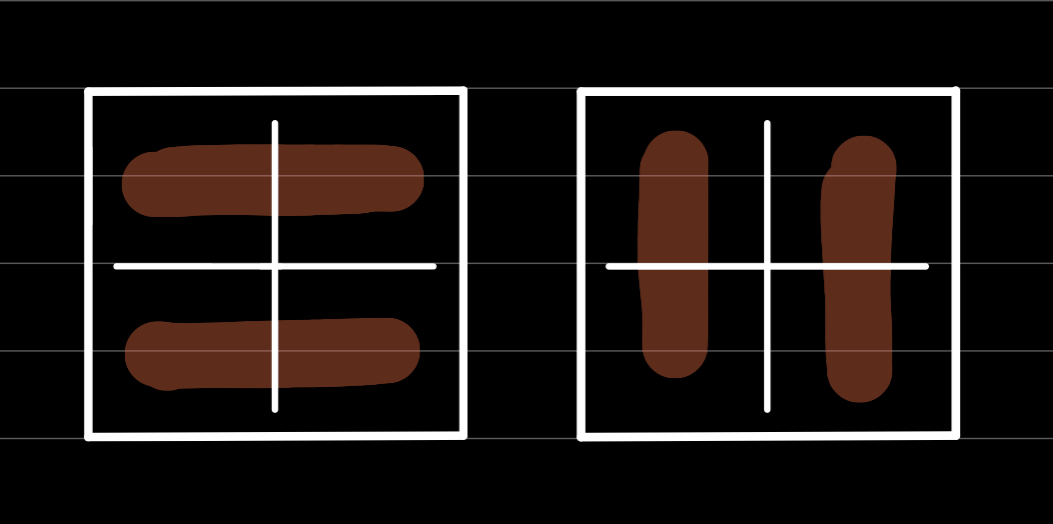

Consider a 2x2 grid representing a certain area in the US. Suppose I task you with coming up with 2 continuous districts. How would you draw them? Well, there’s two ways: you could draw both districts vertically or you could draw both districts horizontally. Pretty simple, right?

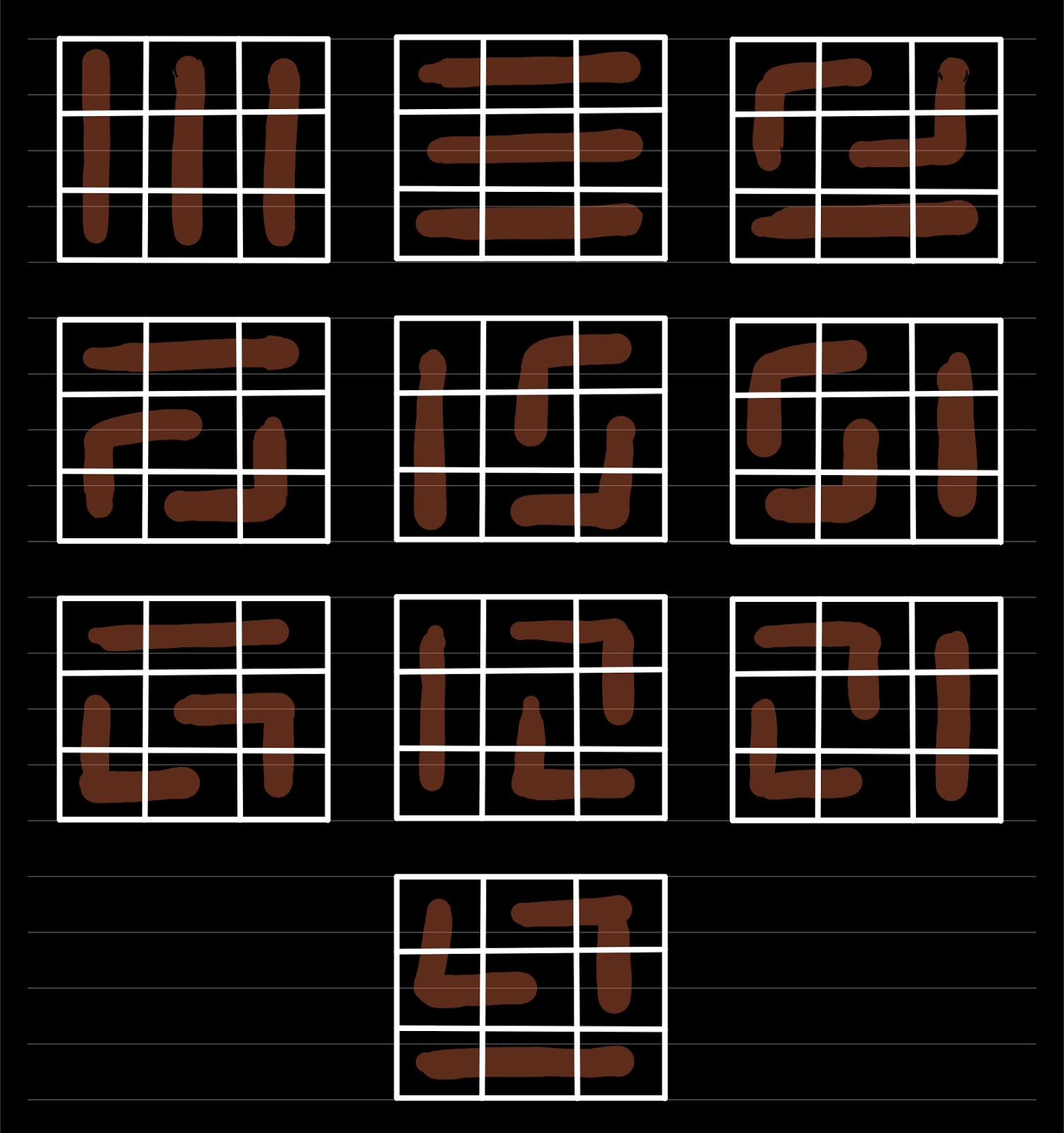

Now consider a 3x3 grid where I ask you to come up with 3 districts. This would take longer than the 2x2 grid but it’s still doable. If you put some thought into it, you’d realize you can come up with 10 different ways to arrange the districts.

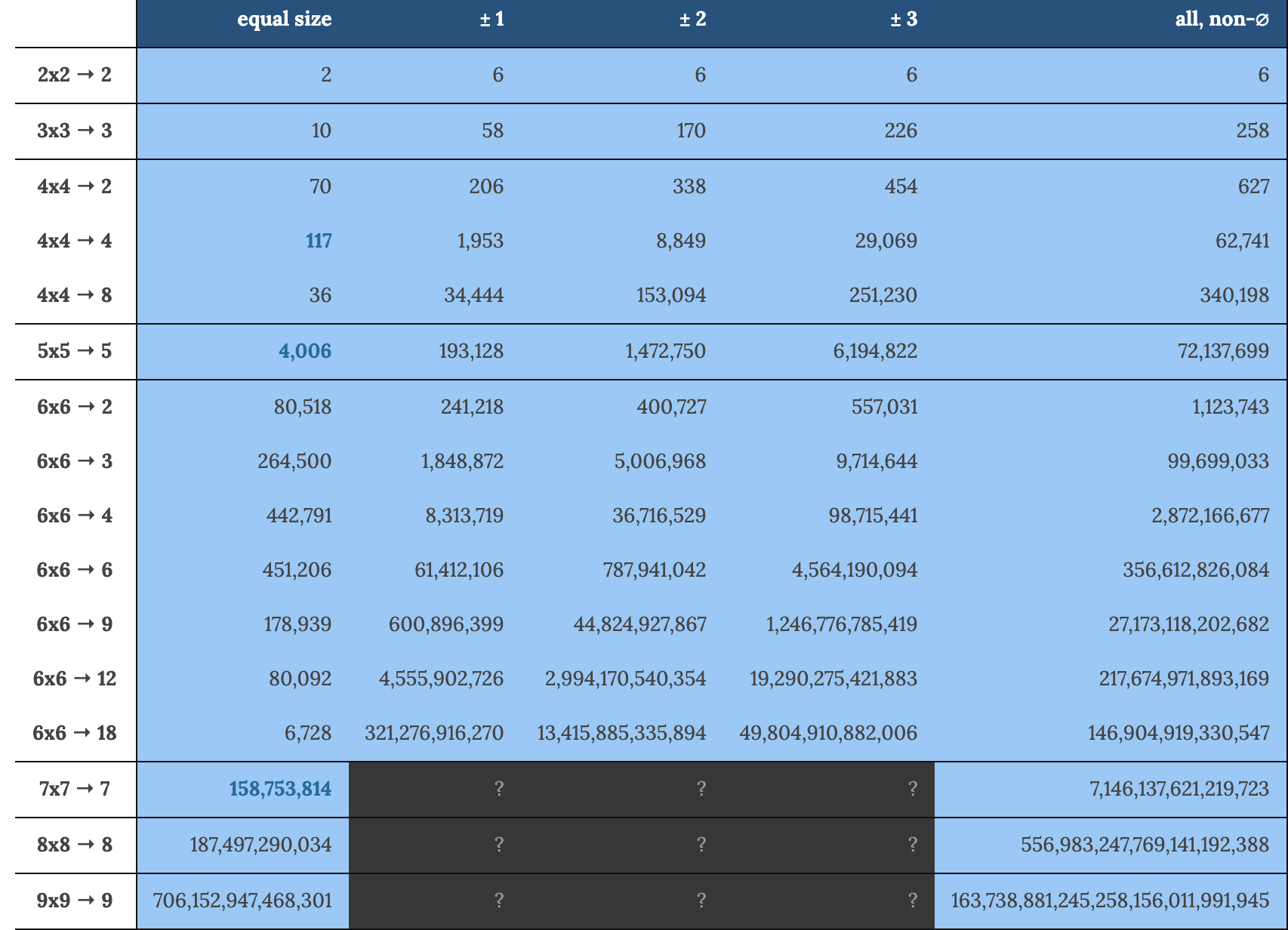

Let’s continue our fun little game. A 4x4 grid has 117 ways to arrange 4 districts. A 5x5 grid has 4006 ways to arrange 5 districts. A 6x6 grid has 451206 ways to arrange 6 districts. Things are starting to get a bit crazy now. To bring this game to an end, by the time we get to a 9x9 grid, we face the overwhelming prospect of having 706152947468301 ways to arrange 9 districts - that’s more than 706 trillion arrangements.

That’s how many possibilities there can be to process when a potential gerrymander comes to your attention. To make this “game” more realistic, let’s also consider possibilities where districts can be of unequal size. As you can imagine, the problem gets significantly worse. I’ll spare you the painstaking details so here’s a nice chart showing the numbers:

Throw ~330 million people into the equation, a two-party system, a lack of border and boundary data, and the important fact that real maps aren’t neat grids like our examples above, and you can see why this problem is impossible to keep up with. After a certain point, detecting gerrymandering/processing redistricted maps is quite simply incomputable - there is no way around that.

That's an extremely scary realization to deal with, at least in my experience. Computers & technology are supposed to be these omnipotent, inexhaustible machines that process large amounts of data at speeds humans could only dream of, but even they have their limitations. So, in the fight against partisan gerrymandering, we’re essentially capped by the processing power of modern-day technology.

As Ron Popeil would say: but wait...there’s more! The gerrymandering problem isn’t difficult just because of how quickly it gets too complicated for our machines; we also need to talk about how easy it is to gerrymander a map.

While the new president of the US is from the Democratic Party and the Senate is a 50/50 split where the Vice-President (another Democrat) is a tie-breaking vote, the US is still under Republican control for the most part. The Republican Party is in charge of 30 state legislatures, whereas Democrats are in control of 18. Similarly, the Republican Party governs/controls 23 states in the country whereas Democrats control 15. Another aspect to consider is the fact that ~54% of the state legislators in the country are members of the Republican Party whereas ~45% are Democratic. That’s a lot of numbers I’ve thrown at you but the point is that while the handful of people at the top are Democrats, most of the country - on a day-to-day governing basis - is run by the Republican Party. Therefore, it is not hard to understand why all the numbers & reports point to the fact that Republicans are more fond of gerrymandering than Democrats; it’s because they can. This represents a catch-22 situation where Republicans are in power which allows them to gerrymander as they wish and because Republicans are free to gerrymander as they wish, they are in power.

The need to highlight Republican control in the country is to make the point that they can gerrymander freely (because they control the states) and that there’s no accountability when they do this gerrymandering (because they control the legislatures). And that isn’t to stick it to Republicans and criticize them - Democrats have done and do the exact same thing wherever they are in power and in control of the state legislatures.

Let’s circle back to North Carolina. Two members of the Republican Party there - a senator named Ralph Hise and a Representative named David Lewis - are prime examples of how easy it is to gerrymander a map on party lines (i.e. partisan gerrymandering). Senator Hise chaired the NC Senate Committee on Redistricting while Representative Lewis chaired the NC House of Representatives Redistricting Committee. In an article for The Atlantic, they wrote that the maps they had changed in NC were partisan and not racial, which they were being accused of. The new maps they had drawn up were intended to support the Republican Party in North Carolina, since they had won power there for the first time in 140 years. Although they exploited loopholes in the Voting Rights Act and the criteria it laid out, their map was rejected by a court on the basis of race. The surprising bit was that in its decision, the court said the maps would’ve passed if “politics, not race, was the driving factor.” What Hise and Lewis found out from this process was that race could not be the primary factor when redistricting, although politics could be - which was their intention from the start, anyways. So, their map was rejected on a technicality because someone thought they were gerrymandering on the basis of race, which they, by their own admission, were not. Secondly, Hise and Lewis noted that they could have gone further and gerrymandered the map in a way that gave Republicans an 11-2 advantage instead of the original 10-3 advantage and it would’ve been passed just as easily. That’s incredibly dark and shows how broken, haphazard, and inadequately prepared the system is to deal with issues like this.

Gerrymandering is also fairly easy to do on a technical level and not just a policy level. Dr. Pablo Soberon from the City University of New York (CUNY for short) has done some fantastic, yet scary, work in this area. There’s a field in mathematics called topology, which essentially studies the properties of different objects/spaces when their shape is changed (or deformed to be more accurate). Here’s an explainer if you’re interested in the math.

Anyways, Dr. Soberon’s area of interest is topology. He recently published a graduate level article/paper where he detailed the simple topological approaches that could be used to intentionally gerrymander a map.

Moving on. To sum up, we’ve established 2 key ideas so far. First, gerrymandering gets unfathomably complex really fast and second, it’s quite easy to gerrymander a map and get away with it in almost any circumstance, as Hise and Lewis show us. That’s a recipe for disaster, right?

Well, it gets even worse. To complete the triangle of doom, let’s take a look into how the absence of a formal, working definition of gerrymandering leads to no-one doing anything about it and paves the way for underground gerrymandering networks.

This might sound weird but when it gets to the judicial level, no-one has any clue what a gerrymandered map is. They don’t even know what “gerrymandering” is at that level. That’s odd because we just defined the definition of gerrymandering in the last section. So, how can it be that there’s no “definition” to work with?

It’s because a technical definition doesn’t help in identifying such maps when there are so many factors involved. For starters, all maps are inherently different from each other. That automatically makes the task of a standard definition quite tricky. And from the last section, recall how many possibilities there are for possible gerrymanders - where do you even begin looking when so many options are on the table? What’s the difference in “gerrymandering” between an original map and one where its boundaries are moved one mile to the right?

It would seem logical for the highest court in the country to take initiative on this issue, given that it affects the whole country. However, back in June 2019, the Supreme Court ruled - in pretty clear terms - that gerrymandering isn’t an issue they have to deal with; it’s something states have to deal with “at the ballot box and in state courts.” This represents another cruel catch-22 situation, as The Atlantic furthers, where the people whose vote is suppressed by gerrymandering are being told that their voice/action is what will put an end to gerrymandering.

However, it isn’t that black and white. Going through the relevant court document (Rucho v Common Cause 2019) reveals that The Supreme Court didn’t just shirk off their burden. Far from it, actually. What the Court argued was that since there is no agreed upon definition or standard of fairness regarding gerrymandering, it is not within the court’s jurisdiction to solve it across the nation. In other words: the Supreme Court doesn’t have a reliable toolkit by which they can strike down or approve maps that are alleged to be gerrymanders. Many disagreed/protested against the decision, but it seems to be an understandable one nonetheless.

This lack of a working definition creates a power vacuum in the gerrymandering market and opens avenues for exploitation. Around the time of the census, members of “The League of Dangerous Mapmakers” travel across the country with their laptops with a particular software for redistricting: Maptitude. Over the years, these dangerous mapmakers have been identified to be key members of Republican Redistricting Committees and included people like Tom Hoeffler, who had been gerrymandering districts in the US for 40 years till his death in 2018. Hoeffler was notorious for going around the country and giving presentations titled “What I’ve Learned About Redistricting - The Hard Way!”, indoctrinating other like-minded individuals and Republican operatives into the dark arts of gerrymandering.

Hoeffler and his crew are essentially gerrymandering mercenaries for hire - members of the Republican Party pay for their services whenever needed and the impact really shows: Hoeffler is personally responsible for some of the nastiest gerrymanders in the country including states like Massachusetts, Florida, North Carolina, Alabama, Virginia, Mississippi, and several others. His notorious, behind-the-scenes work in giving Republicans power in the US has resulted in a majority Republican control in the country and has earned him the infamous nickname “master of the modern gerrymander”.

Although Hoeffler died in 2018 and will not be involved in the 2021 redistricting process, those he has trained in Republican Party will be. The League of Dangerous Mapmakers’ invisible hand will continue to dictate the shape of districts in this country and will cause further partisan plus racial divide and exacerbate the problem of political polarization here. In fact, partisan gerrymandering has gotten so out of hand that key Republican figures in redistricting committees are urging members, this week, to scale back on their mapmaking and be more cautious in the entire process; “pigs get fat, hogs get slaughtered” one member was quoted to say.

To reiterate, all this is caused by the absence of an enforceable, court-compatible standard for gerrymandering. And the overall problem can be summed up as: gerrymandering is terrible for the country and it’s incredibly complex to keep track of, quite easy to execute, and no-one in government has an idea where to begin stopping it. However, as the overview of this project promised, there are a few mathematicians whose promising work may be paving the way for a more equal, fair, and representative future for the citizens of the US and beyond.

Here's an interactive tool that let's you play around with districts and gerrymander as you wish. It's very impressively designed and gives a scarily good idea of how much havoc simple rearrangements can cause.