An Analysis of Court Cases in NC and PA

1. North Carolina - Jonathan Mattingly

Here we’ll talk about the Supreme Court case I mentioned earlier: Rucho v Common Cause. North Carolina’s congressional plans were revealed and many were furious - they called it a clear gerrymander, a violation of the First Amendment, and an effort in voter suppression amongst many other things. Over the years, the case made its way to the Supreme Court, where Duke University’s Jonathan Mattingly was called in to testify about the case.

Mattingly (the chair of the Math department at Duke University) and his team worked on calculating outliers in North Carolina using MCMC. In accordance with North Carolina’s state laws, they established a range of maps that were considered appropriate and/or permissible in terms of balance/power between the Republican and Democratic parties. They generated 24000 maps that fit this criteria and ran simulations of the elections in each one of them using voter data. This is how it went down:

“Using actual 2016 congressional votes, fewer than one percent of the 24,000-plus maps Mattingly’s team generated yielded the 10-3 Republican advantage that North Carolina saw in the 2016 election. Democrats won just three of North Carolina’s 13 U.S. House seats in 2016, even though the votes were closely split 47-53 percent between the two major parties. None of the 24,000 theoretical maps could give Democrats fewer than three seats. In other words, Mattingly says, the General Assembly could not have drawn a map that turned the close statewide vote totals into more lopsided results if they tried.”

To make matters worse, the team also determined that this plan would keep the Republican’s 10-3 advantage intact even if their share of voters went down. Mattinly labeled this as the “firewall effect”.

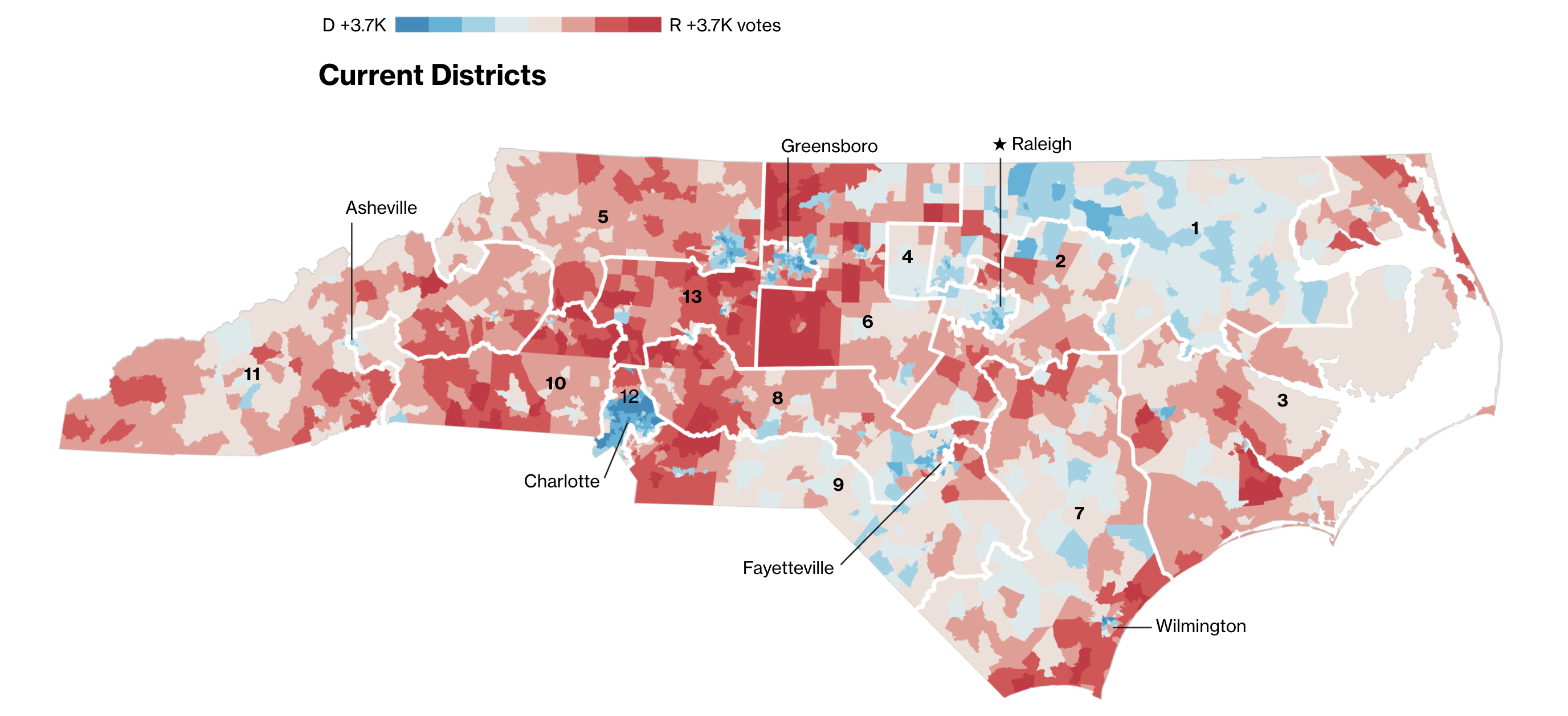

Here’s a map that indicates how much advantage the Republicans have on an area by area basis:

Lawmakers in the case even argued that, on a district-by-district basis, this map resembles an “S” which should stand for the “signature of gerrymandering” because of how bad it was.

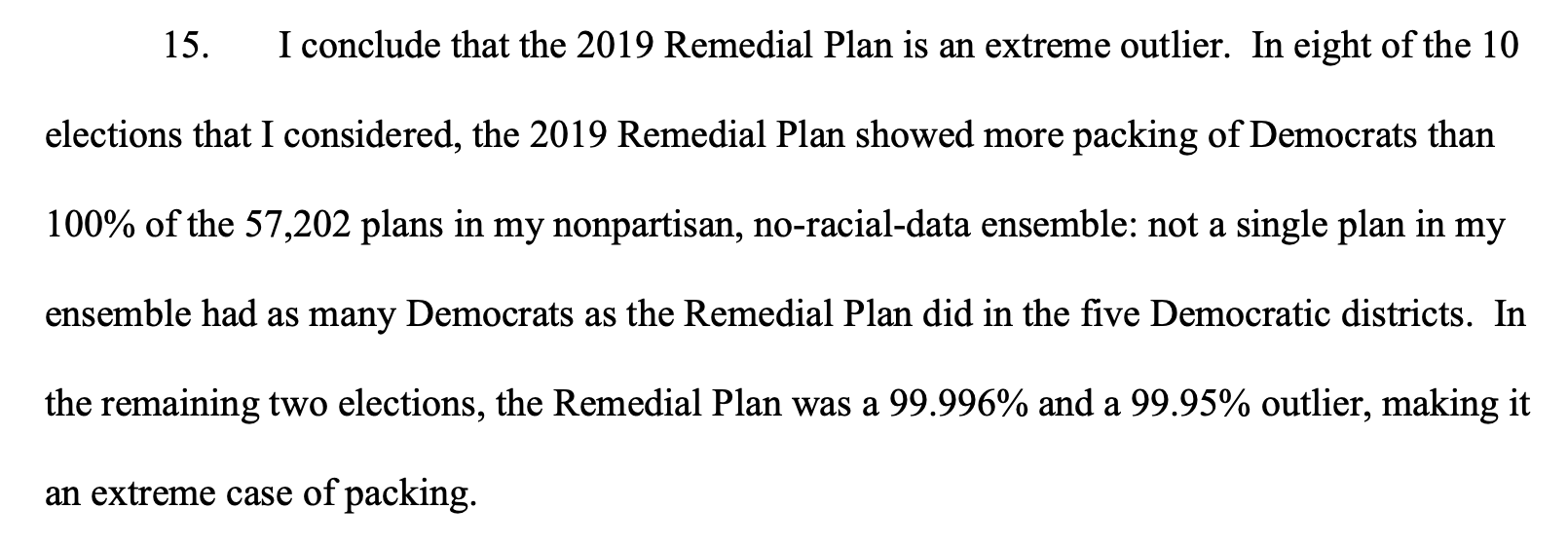

The case for Rucho v Common Cause was heard on 26th March 2019. Mattingly testified with a wonderful 10-page argument on why the map was gerrymandered, with the gist of his testimony as follows:

As we talked about in an earlier section, the Supreme Court didn’t really rule in favor of Mattingly’s argument - they held the case on the basis that lack of a standard for gerrymandering puts making judgements on it outside the court’s jurisdiction. However, the fact that Mattingly’s opinion was sought after, considered, and part of the dissenting opinion on the case says a lot about the MCMC approach to gerrymandering - the future is bright.

2. Pennsylvania - Wesley Pegden

While the North Carolina case occurred at the federal level, the Pennsylvania case occurred at the state level. Another difference between the two is that the Pennsylvania case actually resulted in a positive outcome: the plan had been declared an unconstitutional gerrymander.

“The League of Women Voters brought a lawsuit against the state to argue that the congressional map, drawn by the state’s Republican-controlled General Assembly after the 2010 census, was an unconstitutional gerrymander”.

Again, credit goes to the court for bringing in experts to testify and considering their analysis on the matter. This time it was Carnegie Mellon’s professor of mathematical sciences Wesley Pegden. Wes Pegden didn’t go for the same approach as Mattingly; He “used a different kind of test, appealing to a rigorous theorem that quantifies how unlikely it is that a neutral plan would score much worse than other plans visited by a random walk. His method produces p-values, which constrain how improbable it is to find such anomalous bias by chance.”

In essence, Pegden’s algorithm changed minute details of the map in question, ran the experiment one trillion times to build up the range of all possible maps, and determined that 99.9999999% of the alternative plans were more fair. In other words, only 0.0000001% of all possible maps were as partisan/biased as the current plan - this enabled Pegden to conclude an obvious partisan gerrymander from the Republican side. He goes into a lot more detail in this expert testimony in this TED Talk, if you’re interested.

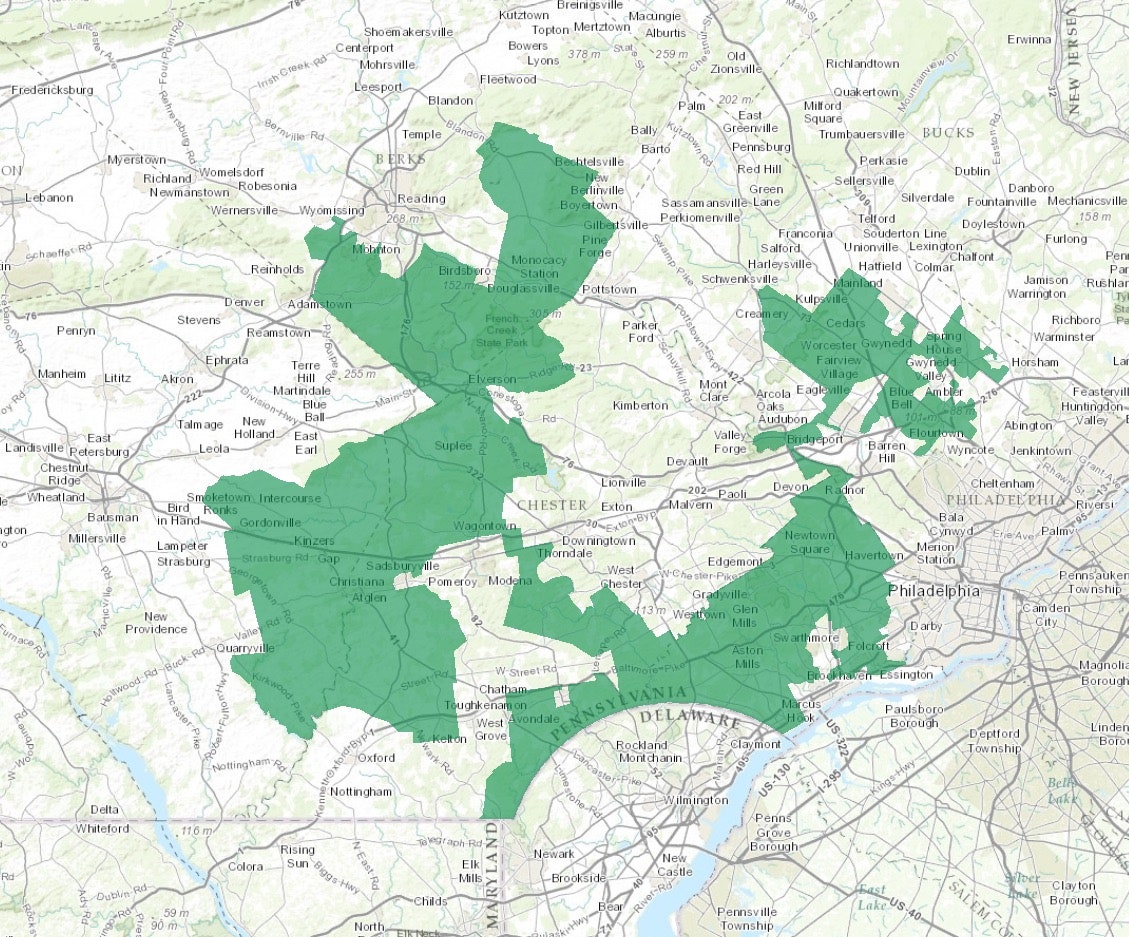

The gerrymandering was so bad that experts started to call Pennsylvania’s 7th district “Goofy kicking Donald Duck”:

But not to despair: the Court seemed to like Pegden’s testimony and ruled in his argument’s favor. The Court sided with the League of Women Voters and declared Pennsylvania’s map an unconstitutional gerrymander: they ordered the relevant authorities to come up with a new plan before the 2018 midterm elections that were coming up.

Another feather in Pegden’s cap is that when Moon Duchin applied her own MCMC framework to this problem (upon Governor Wolf’s request), she reached the same conclusion: Pennsylvania’s map was extremely gerrymandered in favor of the Republicans.

In the grand scheme of things, we can’t really make any conclusions about Mattingly and Pegden’s approaches in relation to each other. It’s not like Mattingly had a less robust approach than Pegden, leading to the Court not ruling in his favor. It’s about circumstances, the arguments being put forward against, the nature of the Court, and unique intricacies that each state presents - it’s an amalgam of all of those things and so much more. What we can say is that these were extremely positive steps in the right direction - this represents a significant shift in the attitudes towards gerrymandering detection and grants MCMC a lot of credibility that only paves the way for more reliance on it.