An Analysis of Gill v Whitford

The Gill v Whitford case from 2017 is a landmark case in the Supreme Court’s history and in the fight against gerrymandering. Why? Because it was the first partisan gerrymandering case that the Supreme Court agreed to hear in more than a decade (the last one was in the mid-2000s when Justice Kennedy said that a workable standard for gerrymandering needs to be developed by someone for cases like these to be solved at the highest level).

Gill v Whitford is also very important because of the clarification that was provided by the litigators regarding the usage of the EG measure - there was a lot of hype and misunderstanding around the EG measure that needed to be aired out. This hype can be seen in the fact that even before the EG measure was tried in a real-world case like Gill v Whitford, it was being touted as a “silver-bullet democracy theorem”, a “gerrymandering miracle drug”, and the “holy grail of election law jurisprudence.”

The EG measure is an incredible tool to quantify gerrymandering and its results often reach the same conclusions as other gerrymandering methods, especially MCMC. However, we do need to apply the brakes a little bit here on the claims being made and the reason as to why that needs to happen. I’ll make that case later on in this section but first let’s take a look at the details of Gill v Whitford and how it went down.

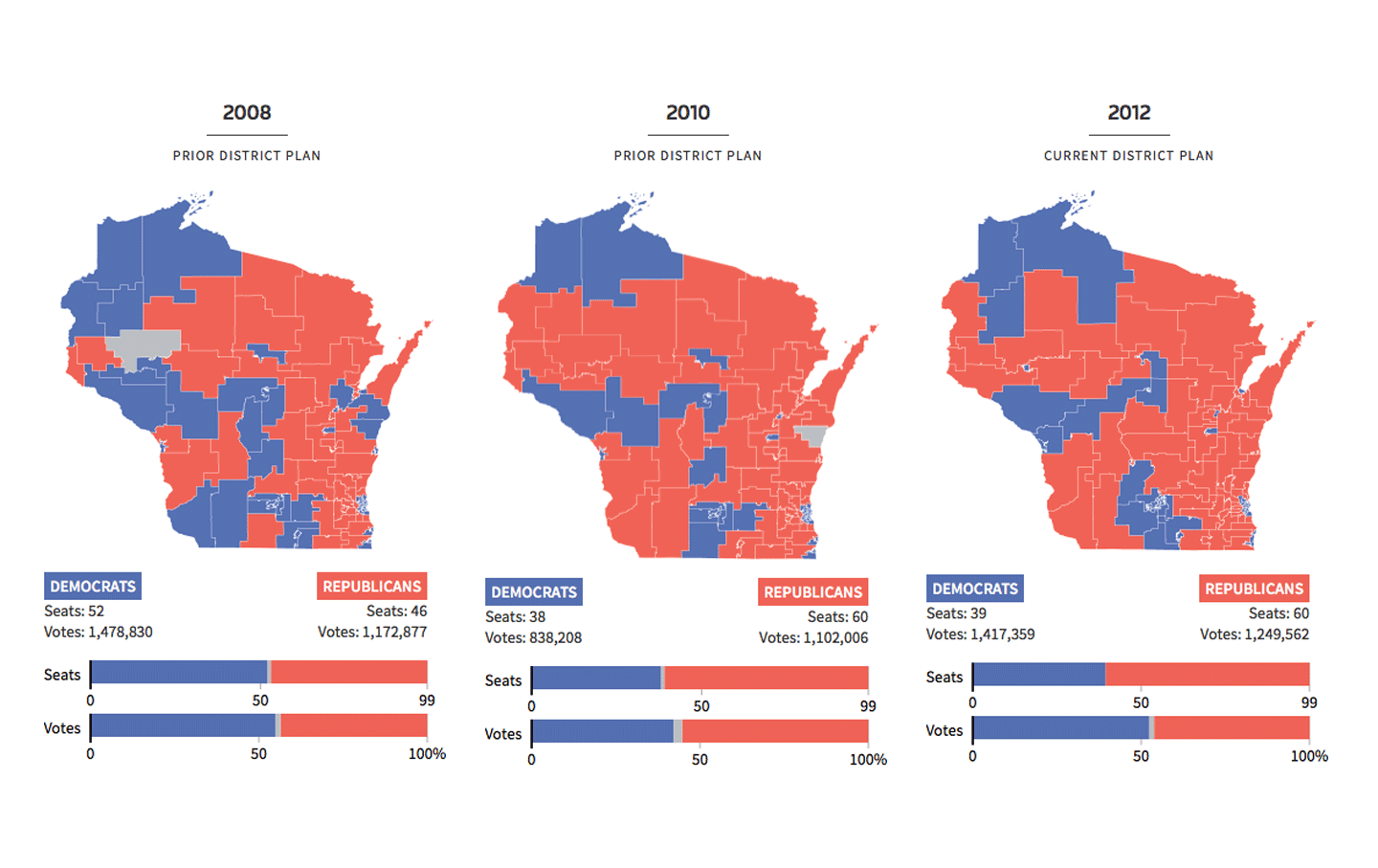

Back in 2017, 12 Democratic voters in Wisconsin brought a case to the courts: they argued that Wisconsin’s state legislature map from 2011 (seen below) was gerrymandered against the Democratic Party. They said this under the orders of Governor Scott Walker, who wanted to cement the Republican power gained in the state after the 2010 elections by packing Democrats into the fewest number of districts. The Democrats based their case on the idea that Democratic Party won 174000 more votes than the Republicans overall, but the Republicans still walked away with a 60-39 majority in the state.

Despite all their claims, the Supreme Court struck down the plaintiffs’ argument. The decision stated that the focus needed to be on the districts that were gerrymandered and not in trying to prove the whole state was rigged as a whole. However, the Court did send back the cause to the district court for reargument: there was enough evidence of gerrymandering to warrant that, at least. Stephanopoulos and McGhee’s formula showed that the state maps in 2011 had an EG of 13% and 10% in 2014, making both of them unconstitutional.

A similar theme from Rucho v Common Cause can be seen here - the Supreme Court simply did not have an official standard to work with. In the official decision, Chief Justice Roberts writes: “This is not the usual case. It concerns an unsettled kind of claim this Court has not agreed upon, the contours and justiciability of which are unresolved. We decline direct dismissal.”

While the case was struck down on technical aspects more than substantive aspects (full decision available here), , it is another step in the right direction. The EG measure continues to grow and bringing it in for a landmark case says a lot about where this fight against gerrymandering is heading.

But I promised you limitations of the measure - and there are many, unfortunately.

Efficiency Gap measures can be volatile in edge cases. If one party has an overwhelming majority in a state, EG will label that as a case of widespread packing by that party. This is explained by the idea that EG doesn’t necessarily take political geography into account: “In Wisconsin, most Democrats are concentrated in cities like Milwaukee, producing lopsided races there. To the efficiency gap, that could look like nefarious packing, when in reality it’s simple demographics. Similarly, if several nearby districts all swung toward one party in a close election year, that completely natural outcome would get flagged as cracking”.

Another limitation of EG is that “in some cases, it leads to unintuitive conclusions. For example, you’d think that a state where one party wins 60 percent of the vote and 60 percent of the seats did things right. Not so, according to the efficiency gap. If you do the math, that state would get flagged for extreme partisan gerrymandering—in favor of the losing party. Perversely, then, the easiest remedy might be to rig things so that the minority party gets even fewer seats.”

A final note I’ll make of this is conceptual rather than technical and one that Moon Duchin highlights brilliantly in her work: “gerrymandering is a fundamentally multidimensional problem, so it is manifestly impossible to convert that into a single number without a loss of information that is bound to produce many false positives or false negatives for gerrymandering.” In essence, the EG is too simplistic, too reductionist to be used as a solitary standard in detecting gerrymanders.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however, In EG’s defense, it was never meant to be the be-all-and-end-all of partisan gerrymandering detection - it was always meant to be used in conjunction with other tools. This can be seen in the fact that while they were laying out the case against the Wisconsin map, Stephanopoulos and McGhee didn’t just rely on the EG; they took political geography into account, they made use of 200 simulations and ran elections in each of them, and still reached the same conclusion that the Wisconsin map was an unconstitutional gerrymander.

It is this nuanced analysis in conjunction with other tools that is the whole point of the EG measure, says Stephanopoulos. He furthers that “the true breakthrough in Whitford isn’t that plaintiffs have finally managed to quantify gerrymandering. Rather, it’s that they’ve used the efficiency gap (and other metrics) to analyze the Wisconsin plan in new and powerful ways. These analyses are the real story of the litigation — not the formulas that enabled them. Since 2004, the courts haven’t even been able to agree on a test, rendering most lawsuits hopeless. However, in a 2006 case, five justices expressed interest in statistical metrics that show how a plan benefits (or handicaps) a given party. The efficiency gap is such a metric.”

Duchin’s critique of the EG measure wasn’t ill-intentioned, of course. It was a case of a peer simply reviewing work that a like-minded individual had created. Duchin and her colleague Mira Bernstein went on to write that the EG is “a famous formula can take on a life of its own and this one will need to be watched closely”. The Atlantic also notes that “the people who study the efficiency gap know its limitations. The real question is whether the courts will also recognize those limits. The danger isn’t the efficiency gap itself, but rather the temptation to look only at the efficiency gap, and make it the effective definition of partisan gerrymandering in the future.”

So, there is a lot of work to be done and it is being done. Variations of the EG measure are being developed and more and more court cases are popping up where expert testimony involving the EG measure is being brought on board.

For the purposes of further reading, Stephanopoulos and McGhee wrote another paper that addressed the concerns being raised against the EG measure. Take a look here.